A Winter’s Tale

Join Trubloff, (the Mouse who wanted to play the Balalaika) as he sets off into the winter snow, on a sleigh, in the pocket of a travelling musician

Join Trubloff, (the Mouse who wanted to play the Balalaika) as he sets off into the winter snow, on a sleigh, in the pocket of a travelling musician

The Trub family live behind the wall of the parlour bar at their local Inn. Travelling musicians ply their trade late into the evening and the young Trubloff stays up to listen. He falls in love with their music and in the hope of learning to play the balalaika he stows away, hiding in the pocket of one of the travellers.

Trubloff – the Mouse Who Wants to Play the Balalaika, is a rich treasure trove of early Burningham work. Renowned illustrator Petr Horáček picks a favourite and describes what it is about this special image that he likes so much

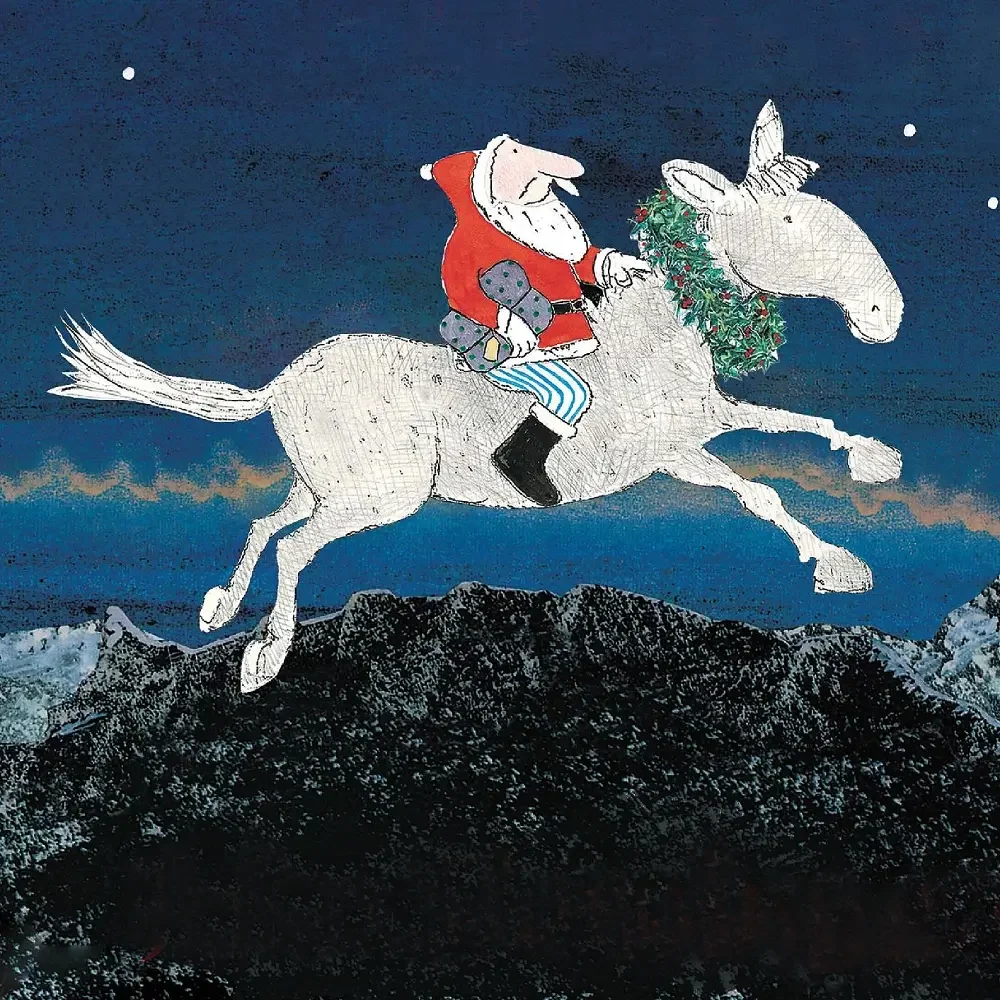

Father Christmas returns home on Christmas Eve exhausted after a day delivering presents to the children of the world. But he discovers one last present in his sack. Out he goes again to make one last trip to far away Roly Poly Mountain, to deliver Harvey Slumfenberger’s Christmas Present.

John Burningham was a big fan of weather and he brought his particular vision to bear whenever he had the chance. In this season when there might well be a hint of snow, we investigate a number of illustrations which show him at his very best

The Sunday Times‘ Childrens Books Expert, Nicolette Jones visited the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang exhibition at National Trust Mottisfont in August. She had this to say …

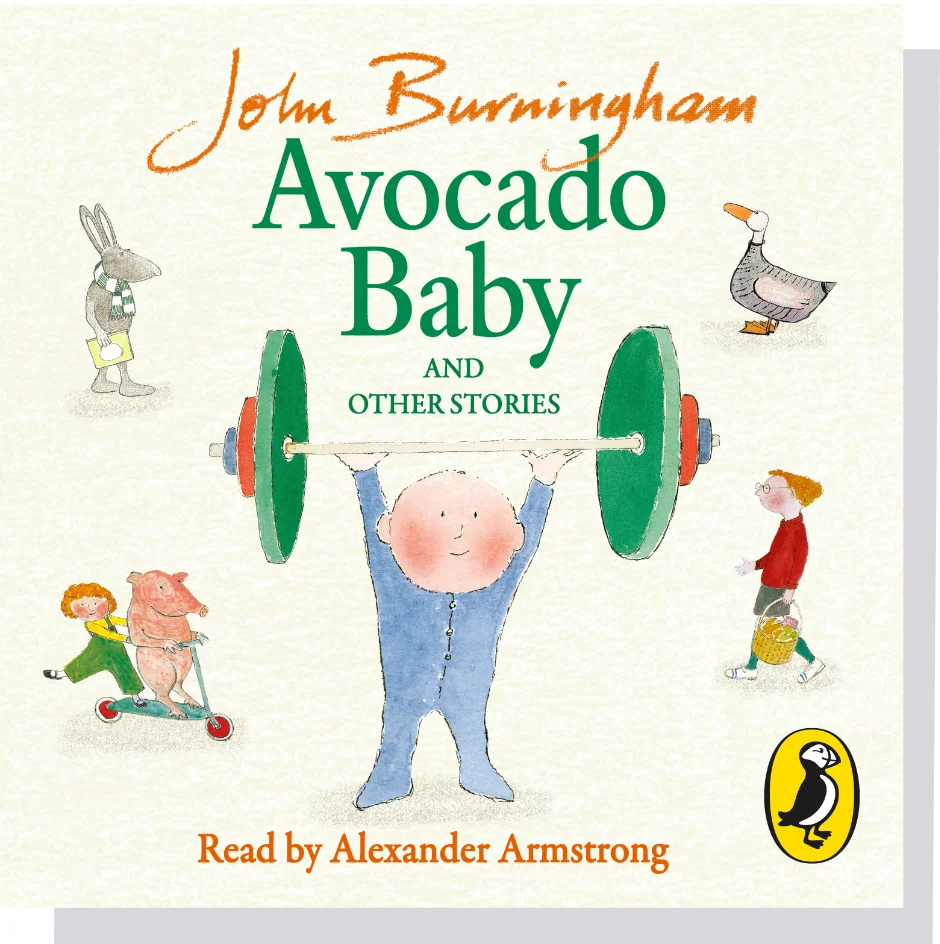

Listen to extracts from ‘Avocado Baby’, ‘Would You Rather’ and Husherbye.

A brand new audio collection featuring ten of John Burningham’s classic stories. Read by Alexander Armstrong.

Celebrate the power of babies (and avocados!) with Avocado Baby, and join Borka the goose on her adventures, amongst so much more in these beloved stories.”

This collection includes: ‘Would You Rather’, ‘Oi Get Off Our Train’, ‘Motor Miles’, ‘The Shopping Basket’, ‘Borka’, ‘Husherbye’, ‘Courtney’, ‘Avocado Baby’, ‘Aldo’ and ‘More Would You Rather’

The Estate of John Burningham has released for sale high quality giclee reproductions of 7 illustrations on a limited print run. Each is signed, numbered and accompanied by a certificate of authenticity.

Download this specially commissioned resource to entertain and inform children of all ages.